Monte Testaccio, Rome. [Photo by StefZ]

Standing on the peak of Monte Testaccio, Rome’s ancient landfill, I am 115 feet above the street. The slight undulation of the rooftops to the north registers the city’s original seven hills. Broken shards of terracotta at my feet seem to extend into the mosaic of red roof tiles at the city center. Looking west, across the Tiber River and along the ridge of Janiculum Hill, I can see the terrace of a building designed by McKim, Mead and White — the American Academy — where I stood just a half hour ago. Stationed for three months as a visiting scholar in architecture at the Academy, I will return often to Monte Testaccio, researching its origins, questioning its relevance and making drawings of its history.

Monte Testaccio is a mountain of detritus in a city of storied hills. The seven hills of ancient Rome were formed by the subtractive process of water flowing west to the Tiber River and eroding a plateau of volcanic deposits. The eighth hill, Monte Testaccio, emerged from a process of anthropogenic orogenesis — the accumulation of trash in the Tiber floodplain; it is constructed from the fragments of nearly 25 million clay amphorae, which conveyed olive oil across the Mediterranean Sea from the provinces of Hispania to the heart of the Roman Empire. 1 The most recent fragments are dated to the third century A.D., when Monte Testaccio was among the largest and most highly engineered waste sites in the world; in the centuries since then, the intersection of diverse activities and constituencies has transformed the cultural identity of this historic waste space.

I am here because Monte Testaccio has captured my imagination as a precedent for modern landfill reclamation. As the discipline of landscape architecture lays claim to diverse infrastructural challenges, municipal solid waste facilities in cities worldwide have been targeted for design interventions such as landfill mining, energy production, brownfield remediation and urban redevelopment. Recent projects have sought to integrate multiple functions and constituencies at waste sites. Most famously, Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island is set to become the largest New York City park developed since 1888, a place where wetland birds share space with horseback riders, public art and methane collection wells. But this type of reclamation needs historical models, and Monte Testaccio is a useful precedent for contemporary theory and practice — an exemplar of both the transcultural practice of manufacturing topography through urban processes and the contemporary aspiration to transform waste spaces into civic terrain.

Top: Climbing Monte Testaccio. [Photo by Michael Day] Bottom: Archaeological dig led by José Remesal Rodríguez. [Photo by Michael Ezban]

Logistics of Olive Oil and Clay

My stay in Rome coincides with an annual archaeological dig led every September by José Remesal Rodríguez, a professor of ancient history at the University of Barcelona. I am eager to peer down into the heart of the landfill. On my first trip to the top of the hill, walking along ribbons of exposed shards, it’s hard to make sense of the terrain. Full-grown trees, scrub grasses and occasional rabbit scat suggest that I am walking on a thin layer of broken amphorae that covers the surface of a natural landform; but the hollow ring of my footsteps is unlike anything I’ve heard on a mountain hike. When I reach the archaeologists’ work site, I discover the reason for the uncanny acoustics. In the open pits, ten feet deep and braced with wood shoring, I see nothing but tens of thousands of broken clay shards. Nearby, the archaeologists have stacked crates of sorted shards, some with inscription (graffiti), others with painted symbols (tituli picti). These ancient markings — names of olive oil producers, shippers, customs agents, weights of oil and amphora, inspection dates — indicate a complex economic and bureaucratic apparatus of food production and transport. 2

Imports of grain, wine and olive oil came to Rome as tax payments from the provinces of the far-flung Empire. Olive oil, which was used for consumption, bathing, perfumes, medicine and lamp fuel, was eventually incorporated into the dole, a ration of subsidized essentials distributed by the government to its citizens. At the height of the Empire, an impressive 18,000 metric tons of olive oil, along with 8,000 metric tons of clay amphorae, were imported annually from Hispania to Rome. The oil was stored in warehouses along the east bank of the Tiber and the clay discarded out back; each year over 280,000 amphorae were smashed and deposited in a series of raised terraces that became Monte Testaccio. 3

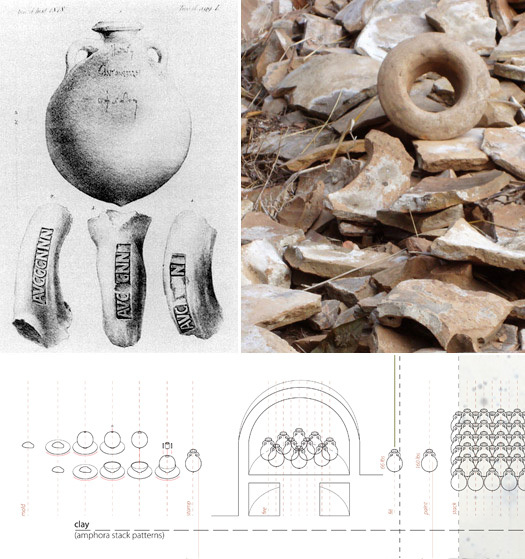

Although the hill consists of hundreds of millions of fragments, I find that within minutes one can easily categorize them into four main types: curved handles, tight radius lips, polygonal plates and pointed base tips. Picking up a thick, trapezoidal plate, I’m surprised to find the impression of three long fingers left in the clay by its creator. More than 80 percent of the amphorae shattered at Monte Testaccio were created a thousand miles away, from clay excavated on the banks of the Baetis River, in the province of Baetica, today the Guadalquivir River in southern Spain. To date, nearly one hundred sites for the on-demand production of amphora have been found in Baetica. 4 These distinctive thick-walled, bulbous amphorae, classified as the Dressel 20, were thrown and fired with pointed bottoms, which enabled three-dimensional tessellated stacking patterns in the hulls of ships and river barges. 5

Top left: Dressel 20 amphora and potters’ stamps found at Monte Testaccio in the 19th century. [From H. Dressel, Ricerche sul Monte Testaccio, 1878] Top right: Amphora fragments. [Photo by Michael Ezban] Bottom: Amphora production and shipping logistics. [Detail of notational drawing by Michael Ezban] Click image to enlarge detail.

In the cortile of the American Academy, a fully reconstructed Dressel 20, about two and a half feet tall, sits outside the entrance to the library. I pass it daily and often imagine what the work was like for the porters and slaves who hoisted amphorae laden with 20 gallons of oil, which weighed over 200 pounds each. 6 The journey was considerable. From olive groves in the province, the oil moved downriver in barges to Hispalis, where the amphorae were transferred to seagoing vessels owned by shipping companies. 7 From April to September these ships carried oil and other goods across the Mediterranean, navigating the swirling Mediterranean currents and harnessing the trade winds. Given clear sailing, the voyage to the Roman harbors of Ostia or Portus would take about nine days.

One day in early fall, I take the train to Ostia to see where the old ships made landfall. What I found was an ancient harbor with no sea. Over the centuries river deposition has added more than a mile of land between Ostia’s wharves and the water’s edge; but the ancient mosaics lining the main square vividly depict porters alighting from ships and unloading amphorae. Ostia’s ruined buildings are mostly roofless; what remains is a city of walls, and I have the impression of walking through a floor plan extruded to random heights. Between some walls lay dolia, massive amphorae, now half buried, which were used for the storage of goods. Now empty, they create a pattern of semicircular voids in the earth.

Roman distributors adjusted for supply fluctuations, often caused by Mediterranean storms, by storing surplus oil in warehouses in Ostia and releasing it upriver to Rome as necessary. I make the trip back to Rome by train in a half hour, and as the landscape streaks by, I imagine the rhythmic chanting of the workmen as they hauled goods slowly upriver in a 22-mile journey that took three days. At the height of the Empire, more than 6,000 annual trips were required to haul all the grain, wine and oil that supplied Rome. Olive oil alone required 2,200 trips each year. 8

Over the course of this intermodal journey the oil and clay would pass through a phalanx of bureaus and labor guilds. The historian David Mattingly notes the involvement of “thousands of people, including imperial officials, commercial associations, individual merchants, various guilds of boatmen, and a great many porters and dockworkers.” 9 At various points the amphorae were inscribed and stamped to indicate points of origin, net and tare weights, signatures of ownership and receipt. Upon arrival in Rome the amphorae were poured into dolia, and empty Dressel 20s were discarded behind the warehouses along the wharves. The 1,000-mile migration of clay and oil that began on the banks of the Baetis River would end with the construction of an artificial monadnock in the floodplain of Rome.

Monte Testaccio and the Tiber River. [Courtesy of Michael Ezban]

Construction and Dispersal of a Roman Monadnock

The date of the earliest deposits at Monte Testaccio is unknown, since archaeologists have never tested samples at the core of the landfill. Recent gravimetric studies show a less dense core, perhaps an indication of haphazard dumping in the early years. 10 It is likely that landfill construction began around 50 A.D., but did not evolve into an orderly disposal process until around 150 A.D. 11

José Rodríguez’s team of archeologists is ambitiously attempting to reconstruct whole amphorae from fragments spread out on a table on the eastern slope. Vise clamps hold six pieces of clay in a three dimensional puzzle. The very fact that they can reassemble an amphora, finding 80 or 100 matching pieces among the hundreds of millions of shards, indicates that these vessels were broken down and disposed of as carefully as they were produced. The archaeologists’ theory is that whole amphorae were broken into halves, then the bottom half crushed into smaller shards and packed into the intact top half. These filled halves were then aligned in a row to form the outer edge of the landfill. The area behind this edge was then filled with broken shards until it reached the height of the intact amphorae. This process of creating an edge and filling up the space behind it was repeated four times; then a new row was begun 8 or 10 meters back, with men and donkeys carrying the next loads uphill. As fresh layers were added, lime was spread to dampen the smell of rancid oil. 12 In the open pits I can see on some shards the distinctive white stains. This process of terracing most likely resulted in a ziggurat-like construction, although there are no extant images of Monte Testaccio in that form. The earliest image, from 1471, depicts the unshapely mound we see today. 13

To get a sense of the landfill at its maximum historic elevation, I clamber to the top and mentally project the road at the base of the hill downwards. Monte Testaccio has shrunk since ancient times. Just as the once dramatic topography of Rome’s seven hills has been tempered by centuries of building collapse and debris redistribution, the ground around Monte Testaccio is thought to have risen 5 to 10 meters due to landslides, flood and the accumulation of detritus. I imagine that Monte Testaccio would have been an ideal refuge when the Tiber overflowed its banks. Indeed, in this largely undeveloped and low-lying area on the southern edge of the city, only the upper plateau of Monte Testaccio, the tip of the Pyramid of Cestius, and the fragmented ridge of the Aurelian Wall would have remained above water during any major flood between the fall of Rome (476) and the canalization of the Tiber (1876-1910). 14

The height of the hill has been diminished through material exportation as well. Repurposing whole amphorae and shards for construction and geo-technical projects was an ancient Roman practice. Amphorae were used to construct the foundations of buildings and roads and to improve water drainage in soils, and they were incorporated as fill in concrete. In a notable example of land reclamation, a depression along the city wall near the Castra Praetoria was filled with amphorae in the middle of the first century A.D. 15 Intact amphorae were also built into the concrete vaults of some notable large buildings, including the Circus of Maxentius. Visiting the ruins of that ancient stadium, a 15-minute bus ride outside the city, I find rows of half-embedded Dressel 20s and 23s exposed in what remains of the groin of the vaults that once supported the seating. An estimated 6,000 amphorae were most likely used to save on material, labor and cost. 16

Embedded amphorae in the ruins of the Circus of Maxentius, Rome. [Left photo by Michael Ezban; right by Mollye Knox]

During the Renaissance, Monte Testaccio became a quarry. Multiple accounts describe clay shards used as a substrate for road construction; the historian Rodolfo Lanciani notes that the north slopes were mined for macadamizing roads in the 16th century. 17 Shards were also exported to construct the vaulted ceilings of St. Peter’s Basilica; the volume of material quarried for that project was so enormous it lowered the hill’s height by several feet. 18 Only in 1744, by government order, did Monte Testaccio cease to serve as a material stockpile. 19

Two Thousand Years Later

In the contemporary globalized wasteshed — just as in ancient Rome — consumption alters topography; physical material from one location is deposited in another, filling in shorelines and flood zones and resulting in mountains and islands. Waste management is a tightly orchestrated logistical operation. Garbage flows along particular routes in accordance with efficiency calculations that weigh disposal fees against distances traveled; it is trucked across state and national borders, exchanged between public and corporate entities, and conveyed from urban to rural zones. Shifts in the volume and rate of garbage flows are triggered by environmental regulations, political action, population densities and economic dynamics. 20 In the United States alone, 243 million tons of trash were hauled by garbage trucks and barges in 2009. 21

Top: Horse-drawn garbage wagon, 1915, and garbage truck, 1954, Seattle, Washington. [Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives] Bottom: Garbage barge, 2009, New York. [Photo by errrrrrrrrika]

Some garbage is earmarked for recycling or combustion, which cuts the volume of the municipal waste stream nearly in half. The rest converges on sites of accumulation: municipal solid waste landfills. The EPA counted 8,000 active MSW landfills in the United States in 1988; by 2009, thanks to stringent environmental standards, there were only 1,900, usually operated by multinational waste-management corporations. 22

Twenty-first century MSW landfills are highly engineered landscapes incorporating layers of sorted material, specific angles of slope, internal water recycling and devices for methane capture. Many now-standard compaction and filling operations were pioneered at the Fresno Sanitary Landfill in California, which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2001. 23 Once MSW landfills reach capacity, which can take many years, they are capped with imported clay; the hill and surrounding landscape usually remain off-limits to the public for decades while toxic emissions are monitored and siphoned off for remediation. The landfill becomes a disengaged monadnock.

In some ways contemporary landfills bear little resemblance to the Roman amphora dump. Monte Testaccio was all clay and no cap. Due to its homogenous composition and advanced age, it is inert, and unlike contemporary landfills, it never emitted methane or leachate, nor did it settle sporadically for decades as its contents decomposed. We also see differences in the vegetation supported by these waste sites. Most contemporary landfills are planted with monocultures of non-native grasses whose root systems will not threaten the integrity of the cap. Monte Testaccio’s slopes support the spontaneous growth of at least 176 species of shrubs, trees and grasses that create diverse ecosystems and microclimates. 24 Yet despite these dissimilarities, the process of Monte Testaccio’s formation resonates with contemporary practices. Like its modern counterparts, it resulted from the waste stream of a transnational network of food manufacture and transportation that ranged thousands of miles and served millions of citizens. Its scale and logistical complexity rivals that of contemporary food distribution and waste systems. Monte Testaccio is the physical byproduct of the flows of materials and the exchanges of goods and services that underpin the processes of urbanization.

Monte Testaccio as Civic Terrain

I’m in the portico of the Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, in line with tourists waiting to test their fate by inserting their hands in the bocca della verite. Several feet shy of the famous statue, however, I’ve spotted my own prize embedded in the wall — a marble tablet covered in Latin inscription. I lay tracing paper over the tablet and rub charcoal over a particular line, moving quickly before I’m noticed by the guards. Slowly, testaccio emerges; this is the oldest known inscription of the word, an amalgam of Latin and Italian meaning “potsherd,” dating from the 8th century. 25 Though the tablet refers to the landfill, the name testaccio was later applied to the entire district around the landfill, which was designed and built from scratch in the late 19th century.

8th-century inscription, Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome. [Charcoal rubbing by Michael Ezban]

The physiographic context of Monte Testaccio has fluctuated dramatically in the two millennia since it was constructed behind the warehouses and wharves of ancient Rome. The completion of the Aurelian Wall to the south and west, circa 275 A.D., incorporated the closed landfill within the city limits and definitively confirmed its urban status. After the collapse of the empire in the late 5th century, the urban fabric of Rome began to shrink back until it was concentrated in the center around the Campus Martius. Gradual destruction of the surroundings buildings left Monte Testaccio in a derelict zone — the disabitato, or uninhabited — for centuries. In these years Monte Testaccio, still within the city limits, was, paradoxically, both urban and rural. The Nolli Plan of 1748 depicts this dual condition — the landfill sits among agricultural fields encircled by the wall. Landscape paintings by J.M.W. Turner and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot in the 19th century also portray an arable “countryside” dotted with urban ruins. 26 It was not until the late 19th century that the area was re-urbanized, during a spate of construction triggered by Rome’s new role as capital of a reunified Italy; Testaccio was then established as a blue-collar ghetto with housing for the employees of a new industrial slaughterhouse.

As I walk through this neighborhood on my way to dinner, the district’s relative youth shows in the wide avenues and the even grid, so different from the medieval and renaissance streets that negotiate the relics and infrastructure of the ancient city. Monte Testaccio itself constitutes a significant break in the urban pattern; yet upon arriving at the base, I note how well hidden it seems, ringed with one- and two-story buildings. Tourists and locals alike can be forgiven for not realizing that this eighth hill of Rome even exists. The shaggy vegetation visible above the roofs and the occasional glimpse of an exposed vein of shards are the only indications of the massive landform.

Circling the hill, I pass high-end restaurants, auto body shops, a small Catholic chapel, residential units and a renowned gay dance club. These buildings butt up against Monte Testaccio, and it isn’t until I enter one — tonight I am meeting a group of academy fellows at Flavio al Velavevodetto — that I get a clear view of the landfill. Through the arched windows at the back, it looks as though the building has been buried in a landslide. Flush against the glazing, from floor to ceiling, is an unbroken wall of amphora shards. When I ask the owner why he’s provided guests this view of rubble, he proudly opens a window and explains that the restaurant is built against the side of the landfill to take advantage of natural cooling during summer. I hold my hand in front of this cross section and can feel the cool air flowing toward me. Warm wind penetrating the loose shards is being cooled as it passes across clay moistened by rain; the sheer size of the hill ensures enough evaporative cooling to keep the landfill temperature about 20 degrees below that of the nearby streets. Monte Testaccio is an outsized air conditioner.

Flavio al Velavevodetto, Testaccio district, Rome. [Photo by Michael Ezban]

On the menu I find the typical neighborhood fare: beef remainders and offal, byproducts of the butchering process, euphemistically called the “fifth quarter.” This is a legacy of the cattle market and slaughterhouse that once occupied the space between the landfill and the Tiber; although the slaughterhouse was closed in 1977, its influence on food culture has persisted. Dishes prepared with “undesirable” cuts for the working-class are now local specialties. 27 Testaccio is still the place to get rigatoni con la pajata (pasta with the intestines of a milk-fed calf) and zampa di vitella bolliti (boiled calf’s feet). The old slaughterhouse, which became a venue for rock concerts and experimental film festivals in the years following its closure, now accommodates an organic supermarket and weekly farmer’s market.

In fact, Monte Testaccio’s identification with food predates the slaughterhouse; beginning in the 17th century, it became closely associated with wine. In an inventive transformation of landfill into civic infrastructure, the municipality allowed the excavation of caves into the hillside; the natural cooling properties of the clay shards made the site ideal for public wine cellars. 28 Close inspection of Lanciani’s maps in Forma Urbis Romae shows over a dozen such cellars, with each owner’s name written perpendicular to the side of the hill. 29 Grotto di Besorri 1680 is inscribed over the current location of Flavio al Velavevodetto, and while the barrel-vaulted spaces in which we enjoy our meal do not date to that era, the series of low, arched ceilings give the rooms a cave-like quality.

After dinner we spill out onto Via Nicola Zabaglia, on the east side of the landfill. Two centuries earlier, the landscape before us would have been very different. Instead of a soccer field and a group of nondescript 20th-century buildings, we would be gazing at a stand of mulberry trees that occupied a large field, the Prati del Popolo Romano, the Meadow for the People of Rome. In early October between the 17th and 19th centuries, the Ottobrate festival, an annual celebration of the grape harvest, was held at Monte Testaccio. The wine cellars and the meadow and mulberry trees made this a fitting location for revelry. Citizens came for singing, drinking, poetry recitals and dancing the saltarello. A high point was the arrival of seven finely dressed women, each representing a district of Rome. Their carriages ascended the landfill, where the women sang: A la Bellona! Semo arrivate alle porte di Roma! To the beautiful woman! We have reached the gates of Rome! 30

Emergent vegetation on the western slope of Monte Testaccio. [Photo by Michael Ezban]

Over the centuries Monte Testaccio hosted many celebrations, both secular and religious. The Ludi di Testaccio (Games of Testaccio) were part of a week-long pre-Lent Roman Carnival held between the 13th and 16th centuries. Thousands would gather on the landfill, using it as a grandstand to views the festivities; these included the Pope presiding over the ritual sacrifice of a bear, a cock and donkeys, intended to symbolize the eradication of the devil, sensuality and pride. Citizens participated in competitions and races. In one particularly depraved game, contestants killed pigs that were then placed in wooden carts and rolled down the landfill’s eastern slope, while the contestants themselves were being charged by enraged bulls. In 1363 the city issued an edict forbidding construction of buildings in the Prati to keep the space free for annual festivities. 31

Monte Testaccio was also the site for an annual passion play. Lanciani describes a procession that started at buildings in the Forum Boarium, which were identified with the houses of Caiphas and Pilate, and culminated at the summit of Monte Testaccio, with enactments of the Passion of Christ along the way. The landfill was chosen for its resemblance to Golgotha, the mount in Jerusalem thought to be the site of the crucifixion of Jesus. 32 The 12-foot iron cross on the summit of the hill today serves as a visual reminder of the landfill’s role in the religious life of Rome in the Middle Ages.

My dinner companions and I arrive at the Via Marmorata to wait for the No. 75 bus, near the eastern edge of a cemetery anchored by the Pyramid of Cestius and the Porta San Paolo. This is Rome’s first Protestant cemetery, established next to Monte Testaccio in 1795 to accommodate the growing non-Catholic population. At the time, this part of the city was considered almost countryside, a marginal site for a minority population, and the burial ceremonies occurred at night to diminish the potential for cultural and religious friction. 33

Monte Testaccio. [Photo by Steve Lynx]

I peer westward between buildings and catch a glimpse of the vegetation at the top of the landfill against the darkening sky. In the days when the open space of the Prati was protected, the hill would have appeared formidable. This fact has made it both a useful target for military training and a strategic vantage for combat. In the 17th century, the Pope’s guard, the Bombardieri, launched cannonballs at Monte Testaccio from Porta San Paolo; one of Lanciani’s map in Forma Urbis Romae shows a large divot in the hill’s southeastern side, along with a note that reads “breccia del tiro dei bombardieri (1600),” which translates as “breach created by the shooting of the bombardiers.” 34 I imagine cannonballs sailing across the Prati and further shattering the clay shards. The landfill saw actual combat at least three times; cannons fired on French troops during the war of Italian unification in 1848 and 1849, and anti-aircraft guns were trained on Allied forces during World War II. 35 The remains of the WWII installations remain near the crest, nestled in the shards adjacent to a massive steel cross.

The bus finally appears through a break in the Aurelian Wall, and we head north along Via Marmorata, the ancient trade road that linked the wharves of Rome with the hinterlands beyond. For centuries, the road has led multitudes past Monte Testaccio — citizens and slaves, pilgrims and popes. I marvel at its many programs and diverse uses: the landfill has been a site of infrastructure utility, religious ritual, commercial enterprise, military operation and secular celebration. And every time it was repurposed, it reinforced the malleability of its cultural identity and its agency in the formation of a distinctive urban condition.

I hear horseshoes on pavement and glance out the bus window. The horse-drawn carriage passing us is trimmed in gold and upholstered in velvet, the type that carries tourists from monument to monument in the center of Rome, but I know there are few tourists here on the southern edge. The carriage is headed for Testaccio, where the horses are groomed and housed in makeshift stalls behind the landfill.

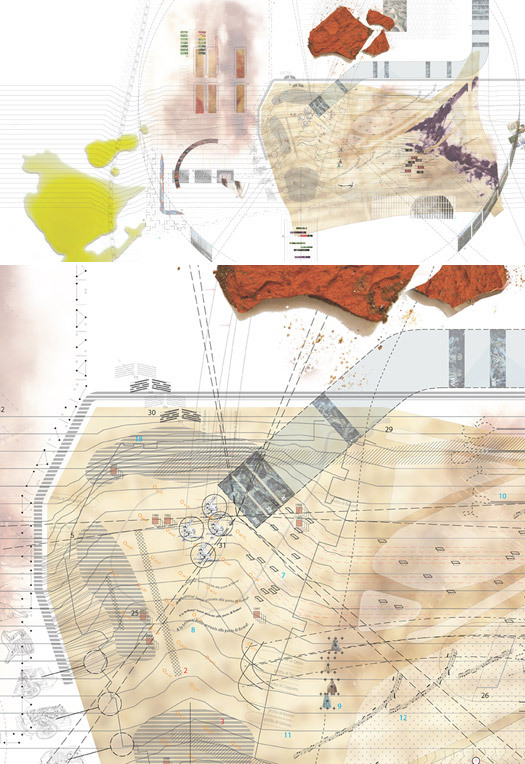

Top: Digital and analog palimpsest of events at Monte Testaccio over 2,000 years. Bottom: Detail of the landfill’s northwest corner. [Images by Michael Ezban] Click image to enlarge detail.

Top: Digital and analog palimpsest of events at Monte Testaccio over 2,000 years. Bottom: Detail of the landfill’s northwest corner. [Images by Michael Ezban] Click image to enlarge detail.

The Promise of Landfill Reclamation: Two Models

Monte Testaccio might seem an unsuitable model for contemporary landfill reclamation, due to its unusual materiality, its distinct socio-economic context and the exceptional duration of its history. At Monte Testaccio, programmatic change occurred through ad-hoc initiatives by religious institutions, governments and militaries, and in many instances was self-organized by Roman citizens. Today’s landfill reclamation projects are initiated by municipal governments, designed by landscape architects in accordance with code restrictions, challenged by an engaged public during design reviews and maintained by parks departments. My intent here is not to valorize a historical European model; instead my goal is to identify particular processes at Monte Testaccio that reflect ongoing contemporary approaches to landfill reclamation and to illuminate challenges inherent in these site transformations. Specficiallly, I would argue Monte Testaccio offers two models for reclamation that demonstrate the potential agency of landfills in the creation of resilient public spaces.

The first model involves the aggregation of many uses and constituencies on a closed metropolitan landfill in order to increase its cultural value. Monte Testaccio is a precedent for an expansive range of post-closure uses; as such it could be said to anticipate a growing consensus among contemporary designers that the transformation of post-closure landfills should incorporate multiple activities, interests and constituencies over time. Fresh Kills Landfill in New York is being transformed over 30 years into a “Lifescape,” designed by James Corner Field Operations, that includes sports and eco-education activities, wildlife refuges and a 9/11 memorial. Hirya Landfill in Tel Aviv, designed by Peter Latz, has reopened as an urban park that mixes ongoing programs for recycling with public recreation and artificial water features. Byxbee Park on the San Francisco Bay, designed by George Hargreaves, Michael Oppenheimer and Peter Richards, interweaves trails and land art installations that interpret the convergence of transportation infrastructure with the Baylands Nature Preserve. A study by the Trust of Public Land estimates that at least 4,500 acres of landfill in major American cities have been converted into parks and public spaces. 36 Too often, however, these projects fail to address a critical question: what unique opportunities are afforded by the composition and properties of the landfill — by an aggregated ground of differential settlement, clay caps and active decomposition?

When the municipal government of Rome opened Monte Testaccio to excavation by the public to create wine cellars, the specific materiality of the landfill was leveraged to great effect. The cooling properties of the loose clay shards, along with the slope of the hill, contributed to the creation of a new form of public infrastructure. Though it could not have been known at the time, this new use would prove generative, enabling grape harvest festivals two centuries later and establishing the pattern of development of restaurants and clubs in the 19th and 20th centuries. In their proposal for Fresh Kills, the design team of Mather + DaCunha and Tom Leader Studio aimed to “reveal the richly layered landscape of Fresh Kills and set in motion the material engagement” of the site, which includes both ancient/natural and recent/cultural deposits. They proposed a schedule of site activities based on material trajectories, including annual journeys during which the public would be invited to trace the path of the last barge of trash dumped at the site and the arrival path of World Trade Center debris. Cuts in an existing berm between urban edge and landfill would establish a dynamic zone for the processing and sale of recycled materials generated at Fresh Kills, a space where “commercialism and recycling will mingle and merge over time.” 37 This proposal thus leverages the historical and future movement of trash and clay to generate new constituencies and inaugurate urban development.

A major concern for the reclamation of metropolitan landfills should include establishing a diverse user base. Remediated sites are sometimes scrubbed of their marginal constituencies, which usually nullifies their civic potential. It’s important to ask: if we value a truly public space, who benefits from landfill reclamation? In the United States, landfills have historically been sited in communities of color and low socioeconomic status. 38 In other countries, landfills attract marginal populations after they are built. In Brazil, for instance, catadores pick recyclable material out of the landfill at Jardim Gramacho in Rio de Janeiro, and live in squalid favelas next to the dump. 39 The landfill’s scheduled closure threatens the informal economies and culture of these working poor, some of whom speak with pride about a lifetime spent combing through the trash, performing an economic and environmental service. Should the ensuing gentrification erase their cultural history?

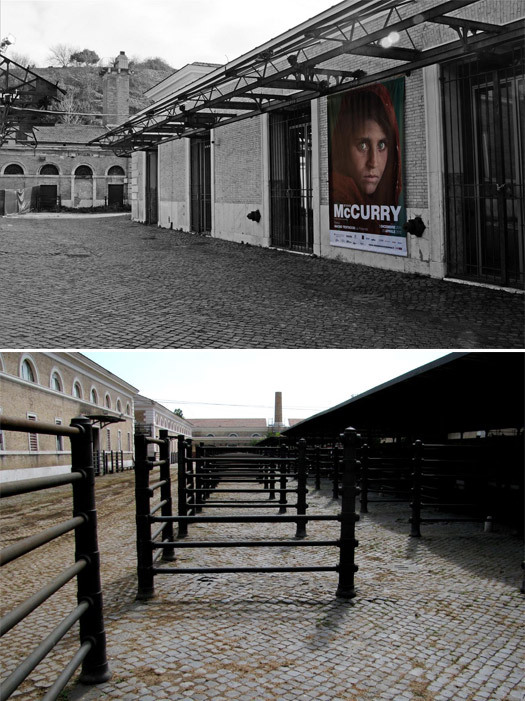

Top: Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome annex in former Testaccio slaughterhouse. [Photo by rickroma78] Bottom: Slaughterhouse stalls, Testaccio district. [Photo by Luigi Giarino]

Monte Testaccio has hosted a range of marginalized populations for most of its existence, but now the constituency is evolving as socio-economic changes bring a greater diversity of activity to the area. The new annex of MACRO, Rome’s museum of contemporary art, is located in the slaughterhouse just yards away from the horse stalls and carriage storage. Adventurous foodies trek to Testaccio for traditional cuisine. Auto mechanics rebuild old Fiats at the base of the landfill as archaeologists piece together amphorae at the top. Ravers dance in the 17th-century caves until early Sunday morning, followed by Catholics attending mass in the chapel next door. Can waste management agencies, municipal parks departments, landscape architects and urban designers work to enable this kind of cultural mosaic on the slopes of contemporary landfills?

The second model that Monte Testaccio provides involves the process of material dispersal. As noted already, one of the crucial public roles served by the ancient landfill was as the quarry for materials used in projects ranging from road construction to land reclamation to St. Peter’s. Contemporary landfills differ from most post-industrial sites; they should be understood not simply as contamination sinks but more expansively as troves of valuable material and potential energy that can prompt local and distant industrial ecologies and urban processes over time.

Laurel McSherry’s and Fritz Steiner’s proposed Center for Environmental Learning and Enterprise integrates an eco-industrial park with a closed landfill and recycling facility in Phoenix. Their project combines aquaculture nurseries, recycling operations and experimental landfill mining practices that function within closed energy and waste loops. 40 In another example, the mining of the closed 16-million-ton landfill at Houthalen-Helchteren, Belgium, a 20-year process set to start in 2014, involves waste to energy conversions and recuperation of 45 percent of the waste material. Interestingly, the project incorporates the phased introduction of native habitat as the landfill is slowly dispersed and converted into parkland. 41 The recent dramatic rise in the price of metals, thanks in part to the construction boom in China, opens new horizons for this kind of landfill mining. To cite just one example: the quantity of waste aluminum — which requires less energy to recycle than to mine from bauxite — has caught the attention of Alcoa. 42

Co-located industrial processes, synergistic energy loops and targeted material distribution suggest new agency for landfills. Those MSW landfills deliberately sited in exurban contexts far beyond metropolitan centers might not be well suited for diverse post-closure cultural programming. Instead, these monadnocks could be broken down over time, serving as temporary material distribution hubs that enable regional and international development. This reclamation model suggests a different role for the landscape architect, that of a conductor of processes and flows of materials over time, knitting together local public and private interests, natural ecosystems and international markets.

Amphora terraces at Monte Testaccio. [Photo by Hans Dinkelberg]

Monte Testaccio is Rome’s feral monument, an ungainly aggregation of material, mythology, interests and events. From the processes of food consumption, waste production and landfill appropriation there emerged over millennia a multivalent terrain that continues to shape urban activity in Rome. As contemporary governments and citizens increasingly demand that reclaimed landfills be many things to many people — energy producers, social nodes, memorials — and also that they interface with local infrastructure, we would do well to study the historical precedent of Monte Testaccio. Nowhere else in the world can you find a landfill that has fostered such a heterogeneous mix of events, interests and users, and done so for so many centuries. Monte Testaccio’s longevity and vitality make it an ideal model of what a landfill can become: an agent of civic engagement and an urban catalyst.This is the promise of landfill reclamation.

Comments are closed. If you would like to share your thoughts about this article, or anything else on Places Journal, visit our Facebook page or send us a message on Twitter.